25.9 CHARISMA CAPITAL

Rizz is the new intelligence

Approximately two hundred people have written some variation of the “In the Age of AI, Taste is the Key Differentiator” think piece, many of which were (ironically) written by AI, most of which do not cite any sources, and all of which are derivative of Kyle Chayka’s work from over six years ago. 1

I’ve already unpacked why I think romanticizing ‘taste’ as a skill is reductive and problematic. Instead, I offered an alternative framework of restraint, intuition, and narrative.

Also —taste is not a reliably differentiated skill. We don’t know whether, at some point, AI advances will be able to effectively generate the semblance of idiosyncratic taste. But we can be quite sure that AI will never be able to replicate the experience of meeting friends for a 6pm happy hour cocktail and ending up on an unplanned New York City Night™ adventure that involves sneaking into a party at the Museum of Natural History.2

Extrapolating from the premise of Aspirational Humanity, I’m proposing that charisma, not taste, may be the most covetable skill in the age of AI. Perhaps your aesthetic sensibility is irrelevant, as long as you can hold a great conversation. AI can style your outfit, but it’s not going to be a helpful wingwoman at the bar. As our external facades become increasingly prone to modification, our personalities may remain the most reliably ‘real’ and ‘human’ part of our selves.

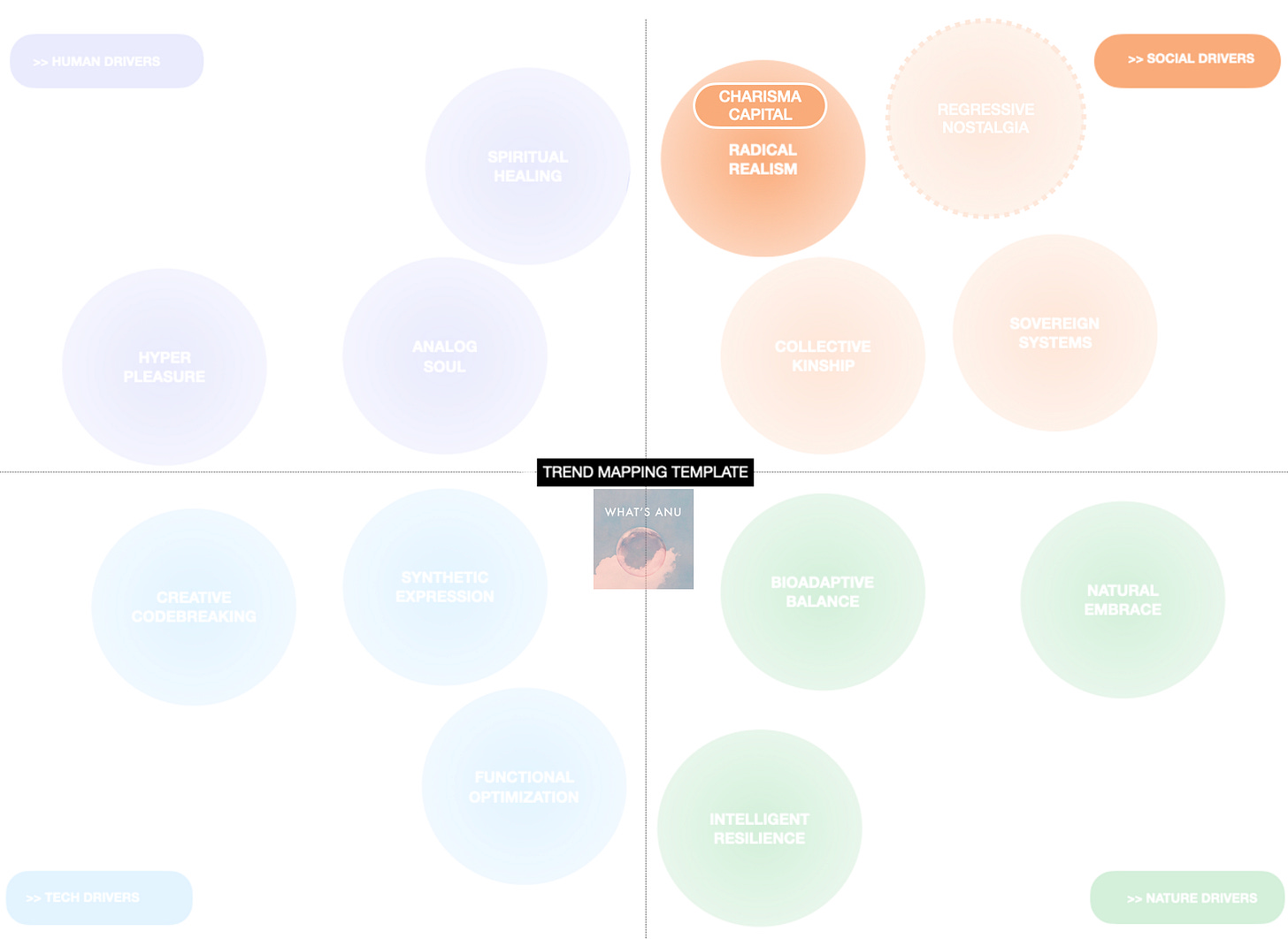

Charisma Capital is the common thread tying together several ideas I’ve been tracking, and I’m situating this within the macrotrend space of Radical Realism.

A couple of weeks ago, citing the rapid rise of TBPN, Emily Sundberg asked, Are we approaching a live video renaissance? And in fact, just a few days earlier, I’d read Kyle Chayka’s piece on ‘Temporal Realness,’ which explored why the recent boom in livestreamed media content is likely connected to our deeper desire for real-time human interaction. I highlighted this in Trend Radar #2, but as a quick refresher:

The only way we can reliably feel (if not wholly know) that something is human made is if we see it coming out of a human body, ideally one that we know physically exists. […] We’re in the wider era of Live Culture, in which we desperately want to know, to be reassured, that what’s in front of us is real. This urge might be semi-subconscious, a drift toward the real-time (or the appearance of such) and a slow dismissal of the pre-made. Livestreamed video is hard to fake, and a live interview is, on some baseline level, authentic.

This analysis caught my attention because it was so clearly linked to Aspirational Humanity — the idea that evidence of humanness is increasingly valuable. Chayka goes on to explain how the demand for live culture has implications far beyond media, noting the surging cultural premium of ephemeral social experiences, whether that be a concert, restaurant, party, sports game, etc. This echos what I’ve previously discussed as Offline Escape, but positions the live-ness of the experience as its most valuable aspect, as opposed to its analog-ness. I’d contend that the demand for live-ness is also connected to the boom in sports viewership and theater attendance. There is a growing appreciation of those inimitable moments where ‘you just had to be there’ because that specific experience can never again be exactly replicated.

The rise of temporal realness is quite interesting when considered in relation to ‘The Death of Partying,’ an popular essay that Derek Thompson published earlier this month, which cites American Time Use Survey (ATUS) findings that depict a drastic decline in real-time socialization:

Between 2003 and 2024, the amount of time that Americans spent attending or hosting a social event declined by 50 percent…For young people, the decline was even worse. Last year, Americans aged 15-to-24 spent 70 percent less time attending or hosting parties than they did in 2003.

Thompson’s recent essay also references an earlier piece he wrote for The Atlantic back in January — The Anti-Social Century delves into how technology has significantly contributed to our societal introversion, and confronts the notion of people choosing AI intimacy over human interaction:

If you find the notion of emotional intercourse with an immaterial entity creepy, consider the many friends and family members who exist in your life mainly as words on a screen. Digital communication has already prepared us for AI companionship…by transforming many of our physical-world relationships into a sequence of text chimes and blue bubbles.

Over the past six months we’ve seen plenty of reporting on the growing popularity of AI companions, which are “ceaselessly attentive, loyal, flattering, and comforting.” This trajectory is somewhat unsurprising. It’s becoming clear that our dependence on digital communications has contributed to the erosion of real-life interpersonal skills. There is a growing inability to cope with, or unwillingness to deal with, the friction that is inherent to most real-life social interactions (i.e. disagreement, discomfort, annoyance).

Most recently, we’ve seen the repurcussions of this behavioral evolution become meme-ified via the ‘Gen Z stare.’ While this has been overblown into another cross-generational spat, the negativity towards ‘stare’ is related to the valid perception that many young people seem unusually overwhelmed by social interaction. For Gen Z, the effects of technology were further exacerbated by the pandemic interrupting formative years of social development, leaving them with “a notable gap in soft skills such as communication, adaptability, emotional intelligence, and conflict resolution,” according to Psychology Today.

Sarah Johnson of TheAkin has coined Reality Inversion Syndrome, or Digital Primacy Syndrome, to describe a phenomenon where Gen Z feels that their online existence is more genuine than their physical reality, which “becomes an anxiety inducing obligation.” Corroborating this, Johnson references the Anxious Generation study finding that “63% of post-pandemic teens show proximity distress – actual physical anxiety symptoms when forced into unmediated social situations.” Her own ethnographic research provides an even more alarming glimpse into teens’ social psyche, with quotes like:

"We met up to shoot content for YouTube. We'll probably text about it later, but hanging out for hours is weird. What would we even do?" – 15yo, Female, Chicago.

"Real-time conversations are exhausting. You can't edit what you say, you can't take time to craft the perfect response, you can't just ghost if it gets uncomfortable." – 18yo, Male, LA.

Months before the ‘Gen Z stare’ became a viral Tiktok debate, Johnson identified how Digital Primacy Syndrome drives “physical world hesitancy—genuine discomfort navigating unmediated social situations.” Young people’s strong preference for digitally-mediated asynchronous interaction at the expense of real-life interaction “means they're losing crucial practice with immediate social feedback.” Johnson also argues that the unprecedented prevalence and intensity of social anxiety among Gen Z has the corollary implication of fundamentally disrupting the typical cultural trajectory we’ve seen throughout history, where youth social scenes and IRL subcultural communities propel creative innovation.

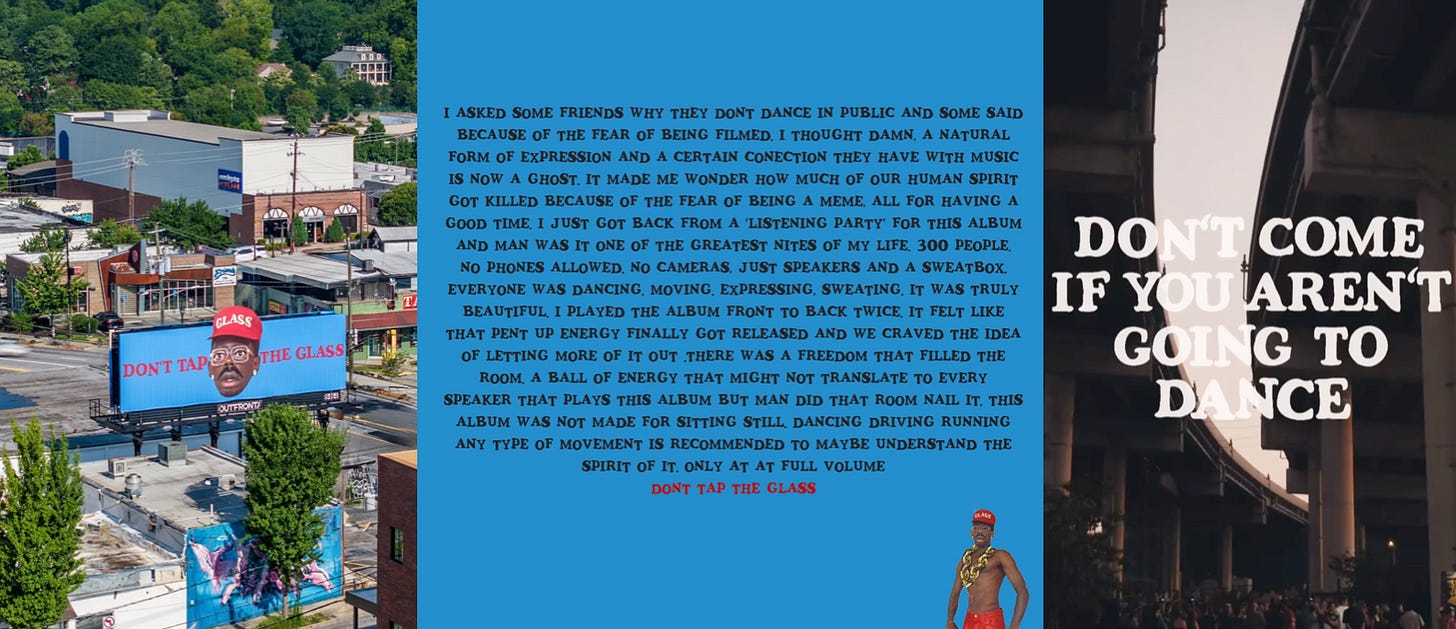

Experiencing the pandemic during a critical stage of neuroplasticity development may have particularly exacerbated the social skills crisis among Gen Z. But technology is the underlying driver, and the ATUS data cited by Derek Thompson confirms that older generations are not immune to its impact on social activity. Beyond the over-reliance on digitally-mediated communication, I think the fear of technology-fueled surveillance is another detractor of uninhibited socializing. Nobody wants to be caught on camera looking ‘silly’ (or cheating at a Coldplay concert).

The decline of socialization is permeating our culture, and in response, we place a higher premium on social connection. We seek temporal realness not only because we are desperate for evidence of humanity in an AI slop-ified world, but also because we are naturally drawn to the increasingly rarified experience of genuine human interaction — whether witnessing a livestreamed podcast conversation, dancing with hundreds of strangers at a concert, or sharing a funny moment at a dinner party. Critically, this also elevates the value of the interpersonal skills involved.

Reflecting on Thompson’s essay, Sean Monahan recently suggested:

…the increasingly difficult task of obtaining a rich and varied social life has only made it all the more appealing. The sense I get today is that more than ever, young Americans realize partying is important. It is in some sense, the ultimate luxury good. When you make something rare, it becomes a true status symbol.

Monahan considers how this intersects with the AI-induced existential crisis currently felt by creatives across most culture industries, from art to Hollywood to media, concluding that “there may be one skill you truly cannot outsource to AI: knowing how to attend and host an event. Increasingly, that is a rare and coveted skill.”

In my Midyear Macrotrend Update, I’d mentioned Offline, an agency that recently launched with the thesis that “community hosts are the new influencers.” Speaking with Amy Francombe for Vogue Business, Offline founder Andrew Roth further explains that, “An influencer or a content creator is focused on producing content — their value is aesthetic or performance-based. But a host creates sustainable, in-person belonging,” by cultivating a sense of trust that is increasingly rare in a world where “people don’t know what’s real anymore.” These community builders, or ‘hosts,’ possess Charisma Capital.

As the ability to hold a conversation or ‘work a room’ becomes less common, it also becomes more desirable. When nobody knows how to have fun at a party, being ‘the life of the party’ is an enviable characteristic. Our desperate desire for genuine human interaction is repositioning interpersonal skills, individuality, and generally ‘charisma,’ as a uniquely significant attribute in the age of AI.

There are some obvious negative ramifications of ‘Charisma Capital,’ like when the cult of personality takes precedence over knowledge, experience, and facts. We’ve seen unfortunate consequences in the political arena, and ‘charisma’ is probably a significant factor enabling Illusions of Intellect (or, why 32K people are still subscribing to an admitted plagiarizer).

But there are also some potentially positive implications, when it comes to moving beyond the overwrought emphasis on aesthetic curation and returning to a sincere appreciation of idiosyncratic character. When everything else, from appearance to knowledge to taste, can be modified or generated or faked, our personalities may become the only differentiator that matters.

As a form of value beyond material capital (what you own), cultural capital (what you know), and social capital (who you know) — Charisma Capital is defined by how you move through the world.

P.S. Apologies for the clickbait-ish title and cover pic, if you’re on the app 🙈

Not my usual style, but it’s a fun little experiment inspired by Annie Kreighbaum’s sharp analysis of last week’s Substack plagiarism scandal…

Illusions of Intellect explores the prevelance of AI-assisted writing, and the epidemic of quasi-plagiarism, on this platform, including how this viral “taste” essay heavily references this article and this post without crediting either.

Fond memories from December 2015.

I also think certain countries and subcultures will excel in the soft skill. When I was in Croatia, how the interacted with social media was so different. Cause most of the apps are localized with only the most viral foreign content breaking thru. Your ability to be one way online and another offline is diminished. And so many other factors: third places, friendships, hustle culture- most countries outside the US don’t get paid for their content and thus the machine is different.

Amazing analysis! I think this could also tie into collective effervescence, and really hope we can have more of the "you just had to be there" moments irl instead of watching it all unfold on a screen.