25.8 ILLUSIONS OF INTELLECT

Due diligence

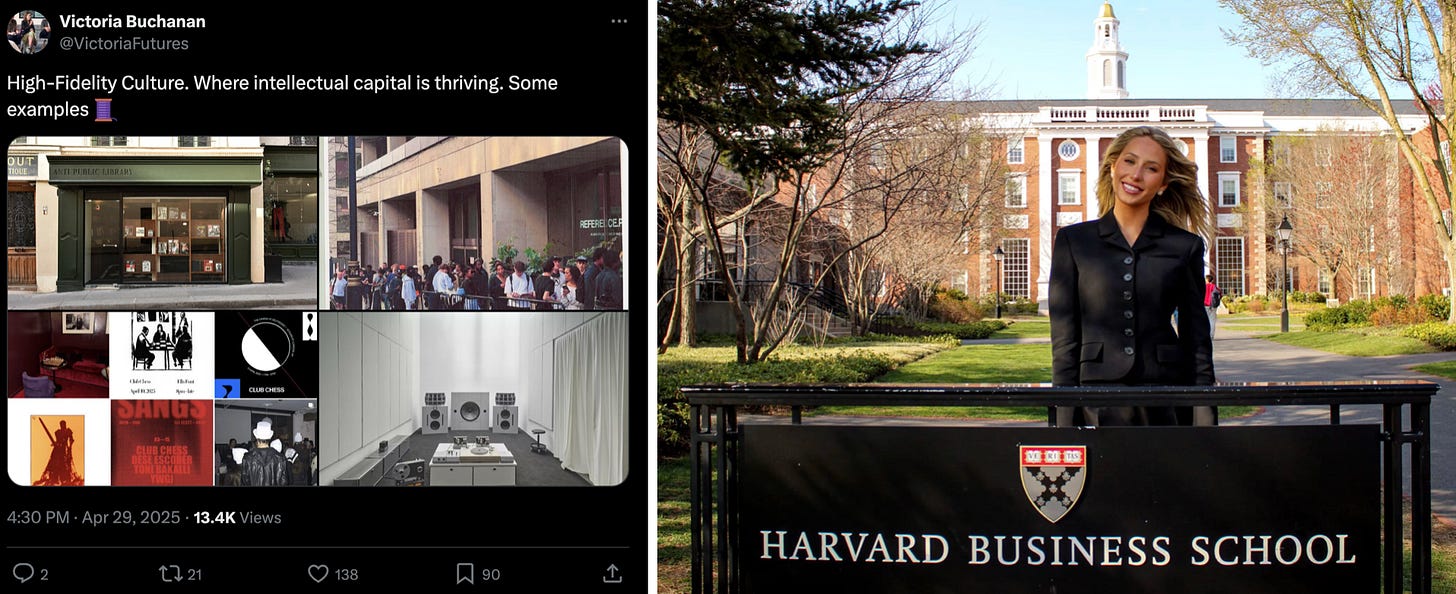

Intellectualism is having a moment. Back in January, I highlighted the ‘literary revival’, encompassing branded zines, brand x book club collabs, and brand libraries, as a trend to watch for continued acceleration this year. Over the past few months, I’ve seen further developments noted by Victoria Buchanan on high-fidelity culture,

on Tiktok oracles, on celebrities chasing HBS photo ops, on the girlboss podcast boom, on the rise of the infotainer, on authors in fashion campaigns, and on wisdom signaling.1Victoria’s articulation is closer to the root of the trend: in an age of superficiality, deep knowledge of niche subjects becomes sought after. But observations from Nikita, Ochuko, Emily, and Charlotte indicate how this idea is quickly diluted: the semiotics of knowledge are used as a signaling device to create idealized Illusions of Intellect with no real depth.

This brings to life a tension I had noticed when first writing about the ‘literary revival’ but didn’t previously mention — there’s a dissonance between the aspirational portrayal of intellectual aesthetics and the worrisome data about a literacy crisis amongst young people. And more recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about how the popularity of superficially signaling knowledge intersects with the increased accessibility of AI — a powerful tool for feigning intellect. I had started drafting this post the weekend before Apple’s WWDC event and their release of a research paper investigating the limitations of artificial intelligence in complex logical reasoning, entitled The Illusion of Thinking.2

Propelled by the rapid acceleration of AI usage by the general public, Illusions of Intellect can be mapped to the Synthetic Expression macrotrend in my framework:

When I originally developed this concept, it was built out of drivers like post-truth era misinformation and metaverse hype that birthed burgeoning aesthetics blurring the boundaries of digital and analog realities, from virtual fashion and AI art to the works Ines Alpha and Tomihiro Kiro. Now, we’re witnessing the macrotrend of Synthetic Expression move beyond visual aesthetics and infiltrate research, writing, and ‘thought leadership’ to create Illusions of Intellect.

Apple’s paper focuses on the complex technological issues hindering AI’s capabilities, but these limitations should be obvious to anyone who has tried experimenting with models like ChatGPT. I have a couple of personal anecdotes of how this became apparent to me. Once, after hearing that people were using AI for astrology readings, I decided that would be fun to test out. What transpired was not exactly fun, but quite funny. ChatGPT told me I’m a Sagittarius Rising. When I replied that this was wrong, it proceeded to claim I’m a Scorpio Rising, and tried to defend why, before pivoting to suggest my ascendant is “most plausibly in Gemini or Cancer,” and blaming me by arguing that I must have provided the incorrect birth time or location. When I reconfirmed those details, it stated that my “Rising Sign is almost certainly Capricorn.” Finally, on the *sixth* attempt, it came up with the correct answer. I questioned why it had lied:

Every time I mention this issue to someone in conversation, they respond with their own unfortunate tales of AI-created misinformation. A story similar to my astrological woes was published by

earlier this month. At the Future Commerce summit last week, mentioned how testing the potential for Perplexity to aid in research for landed him with a useless list of fake links.But either a lot of people remain unaware of these issues, or they just don’t care. A couple months ago, someone tried to personalize a pitch email to me with a quote from Regressive Nostalgia…except it was not real. After wondering why I couldn’t recall my own writing, I ⌘F’d my own essay to confirm that I did not, in fact, publish the sentence “quoted” in this email (although it’s a lovely summarization of the piece).

A pitch email is fairly innocuous. What I find more worrisome is how quickly and indiscriminately people have adopted AI as a writing tool. While its pervasiveness among college students has been widely reported, I’ve seen less discussion about its broader pop cultural impact. As AI becomes the key to rapid pseudo-intellectual creation, both its repetitively circular logic and its misinformation hiccups begin to permeate culture at an unmanageable pace.

Some of the effects are playing out here in the micro-ecosystem of Substack. We’ve been inundated with visual content for over a decade at this point. But now, we’re also wading through a sea of rambling thought pieces, many of which don’t actually say anything new, and function only as Illusions of Intellect.

This piece on ‘taste’ has gone viral — with over 5K+ likes, it shows up on my notes feed at least once a day. In my opinion, it doesn’t really say much at all (shoutout to

for confirming that I’m not crazy). But I did notice that it uses the exact same three terms (curation, restraint, and discernment) as this article published a few days earlier.Did the later piece copy the one published earlier, or did the writers come to the same conclusions independently? Why did the later piece resonate with 5,000 people while the earlier one has less than 200 likes? Did one or both of these writers use AI, and if so, did that influence the reader response? Does it matter?

Most notably: neither of the above pieces contain any citations, footnotes, or links out to external sources.3 This bizarre practice (or lack thereof) suggests these writers have immaculately conceived their ideas completely independently of any external inputs (which is impossible). We don’t live in a vacuum. Our thought processes are inevitably influenced by the media we consume, and we consume a lot. What evidence led to your conclusions? How can I trust your perspective without knowing what inputs informed it? Many of these writers are performing academic analysis while ignoring its core tenets.

In a recent email conversation,

pointed out how the social media fueled ‘personal brand’ dynamic “forces people to focus on having authority, which you can't have if you cite someone else…thoughts are encouraged more than facts and citations.”4 Practices that previously assured credibility are now dismissed as infringing on the superiority of one’s personal brand. As writes, “The most dangerous aspect of this dynamic is that it rewards intellectual absolutism…This breeds an ecosystem where intellectual humility is penalized, and performative confidence trumps genuine inquiry.” Lack of academic rigor, including depth of research and transparency of sources, also contributes to repetitive clutter. It’s why you end up reading a dozen articles on the same topic, with none of them referencing each other or including any citations. We are all exposed to the same cultural evidence leading to similar conclusions, but admitting this would risk compromising the facade of authority.Even when writers ostensibly link to sources, I’ve noticed they are often incorrect. Here’s an example, which links to a Bank of America investigation and Brooks Bell study:

I was genuinely intrigued by these claims and wanted to dig further into the details for use in my own writing. So I tried to find the original information in these sources. It was a fruitless endeavor, because I eventually discovered the data comes from an Intuit Credit Karma report, which was never mentioned in the article quoted above.

AI can provide statistics to back up any idea you want to write or speak about. But there’s no guarantee these statistics will be real, or accurately sourced. I don’t personally think it’s an issue if someone wants to use AI to aid in their work processes. But I believe using AI without corresponding due diligence is problematic and irresponsible. It contributes to a crisis of misinformation by perpetuating theoretical contemplations or subjective observations as objective truths.

In his essay, Everything is Default Fake, Ruby Justice Thelot writes about how the technology-driven blurring of visual reality has warped our perception of the trustworthiness of images and videos. This same analysis is similarly applicable to writing and thinking. And uncritically embracing Illusions of Intellect can be particularly dangerous when academic institutions are already at risk.

More analysis of this paper’s implications is available via

(Computers Can’t Think) and (A Knockout Blow for LLMs?).My eight grade history teacher would be appalled.

Maybe it's because I'm a strategist but I obsessively link and source everything I write about. If I don't have proof of something I won't write it, plain and simple.

Glad you went ahead and finished this! Very timely. Sparked many, many thoughts, but in the name of tasteful discernment, I'll curate my words like so:

post-GPT ubiquity, we have to assume that everything is fluff on here, until proven substantial. Even viral long reads. Even long reads with links. Even long reads by seemingly credible people. Even long reads liked or restacked by credible people! That’s the wild part for me. So, as with any other engagement-based platform, content on here is just entertainment until proven informative. Easy to say that of course…

I think the stickier side of this topic is when it comes to research. Firstly because AI-assisted writing will undermine what’s out there to quote and cite in the first place, and secondly because even the AI research tools that work, like Deep Research, have drawbacks for research quality: http://archive.today/2025.06.22-020625/https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2025/02/13/the-danger-of-relying-on-openais-deep-research