25.10 HUMANWASHING

Post-Reality & A Hierarchy of Humanness

Back in May, I wrote about Aspirational Humanity, or the idea that, as artificial intelligence hyper-flattens mass culture, anything denoting evidence of humanity becomes exceptionally desirable. At the end of that essay, I noted the idea of ‘humanwashing,’ which speculatively came up in a conversation with Philip Teale:

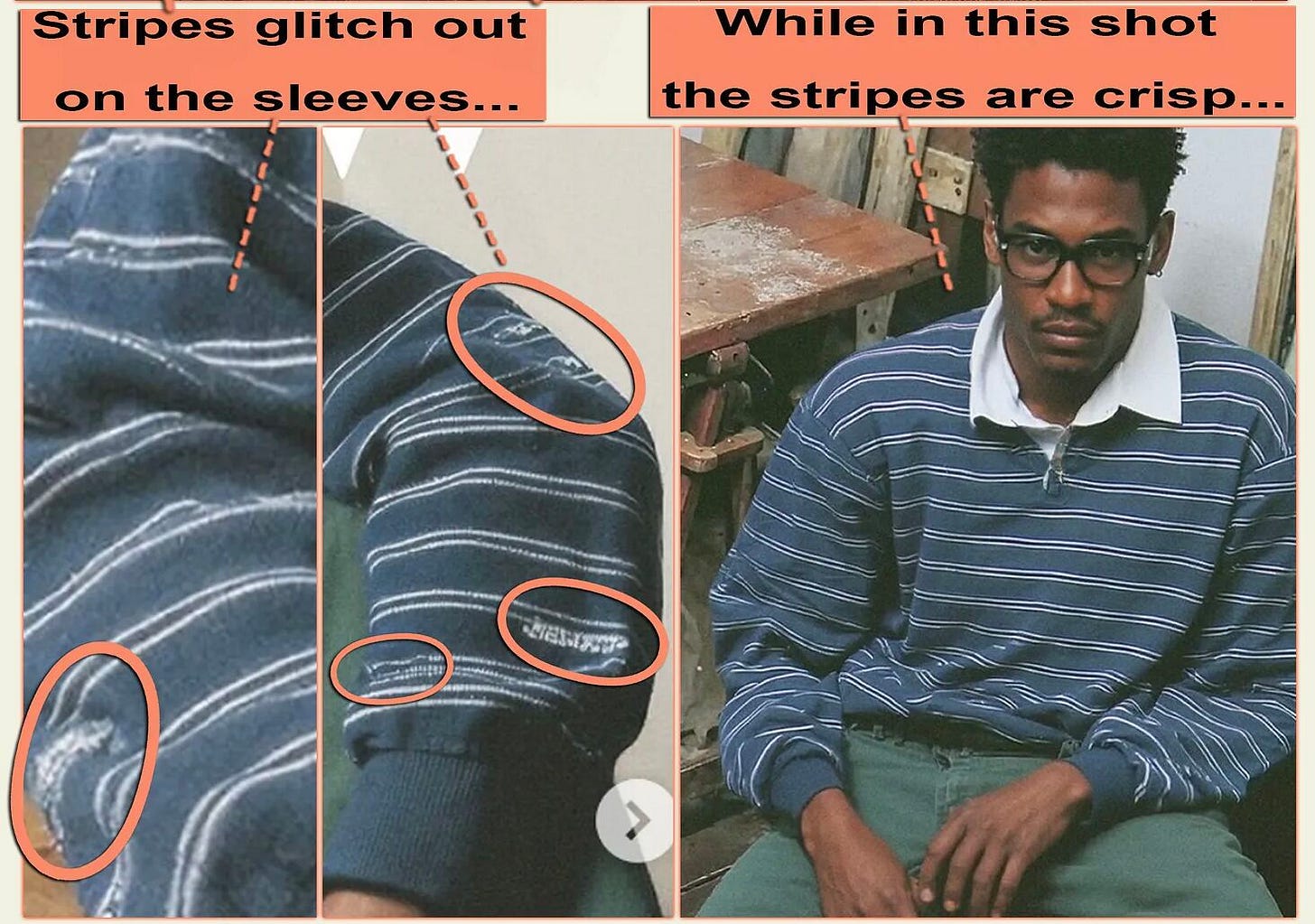

Later, in September’s Trend Radar #5, I highlighted J.Crew’s AI-generated ‘vintage catalog’ dupe as a key signal that humanwashing is here.

Since then, both Philip and I have noticed the term gaining traction on LinkedIn and Substack. Yet we can’t seem to find a clear outline of humanwashing in a consumer context — no essay or article on the topic that could be cited as reference. So we decided we should probably create our own.

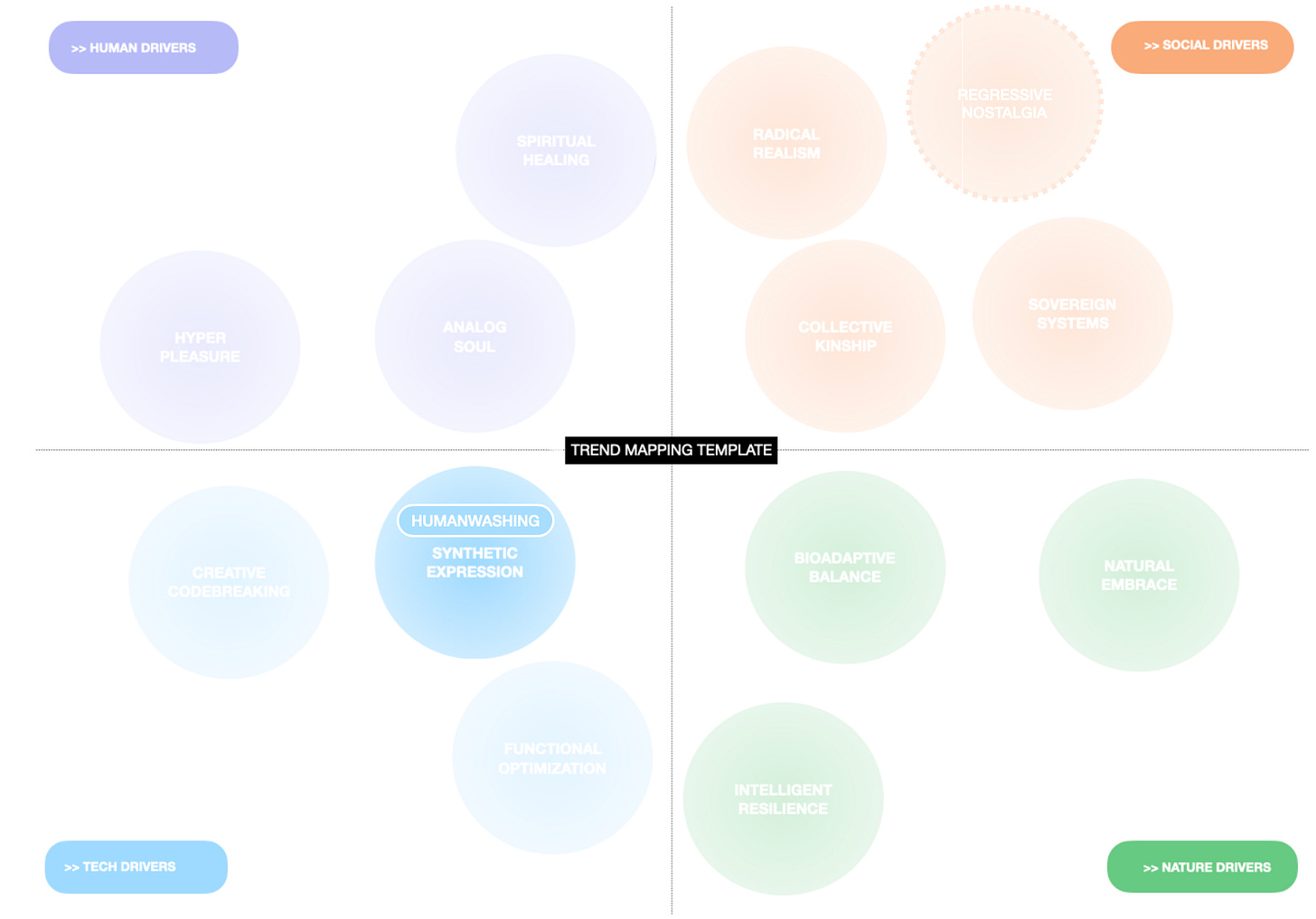

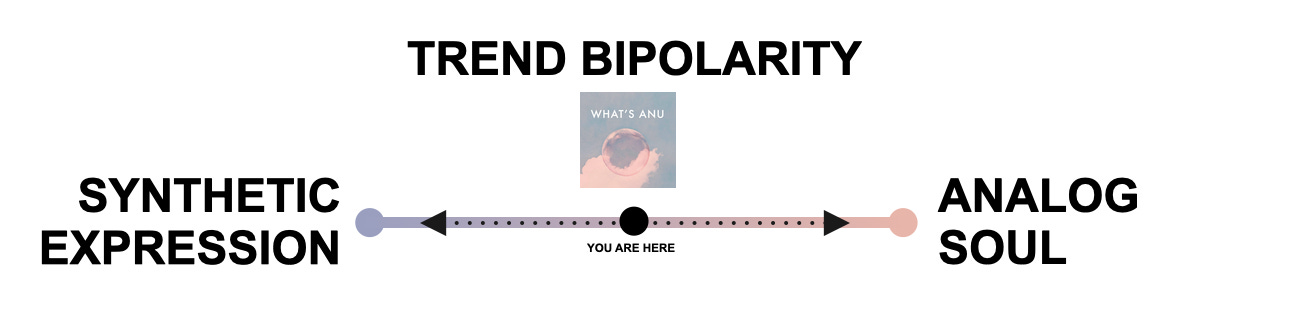

Humanwashing can be mapped to the Synthetic Expression macrotrend in my framework: the performance of synthetic warmth to evoke humanness.

When I originally developed the idea of Synthetic Expression a few years ago, it was rooted in the burgeoning aesthetics blurring the boundaries of digital and analog realities, from virtual fashion and AI art to the works Ines Alpha and Tomihiro Kiro. These examples enthusiastically explored the possibilities of futuristic tech-enhanced aesthetics.

But now, with AI’s outputs feeling increasingly uncanny, consumers are voicing discomfort with synthetic creativity. In response, we’re seeing an evolution in how these technologies are being framed — less sci-fi maximalism, more humanized familiarity. Enter, humanwashing: when brands perform humanity as a facade, while embracing AI in the background.

— A.L.

The Origins of Humanwashing

In 2021, professor of business ethics Peter Seele noted in a Medium post how Boston Dynamics’ robots were being presented online as entertaining and friendly. A video of their robots dancing, filmed at the company’s HQ, had gone viral that year. A few years earlier, their robot’s “shelf-stack fail” made the news for its clumsiness.

Through content like this, BD was deliberately projecting human-like qualities onto its robots, Seele suggested. Given the company’s ties to sectors like defense and industrial robotics, this was striking. He called this the “humanwashing of machines,” as an analogy to greenwashing — a surface illusion to charm away “adverse or harmful characteristics or perceptions.”

Then in 2022, Seele and two colleagues put out a paper formalizing humanwashing as a corporate communications strategy. When an AI-enabled machine is anthropomorphized, the humanlike surface can obscure what the machine actually does. This lets companies capitalize on the information gap between what they know internally and what outsiders assume, using presentational choices to steer attention away from their machine’s real capabilities. That paper was published just months before the GenAI industry began pushing humanwashing even further.

Humanwashing in the Consumer LLM Era

After ChatGPT was released in November 2022, the logic of performing humanity seeped into the marketing, design, and even the ideas behind consumer AI products. As the number of companies developing and leveraging LLMs surged, consumer appeal became as much about emotional realness as practical usefulness. We’ve broken down humanwashing into the following categories, with examples for each:

Made to Look Human: When brands harness human craft and aesthetic comfort in how they communicate and present their AI products

Claude’s “Keep Thinking” ad presenting a global narrative of human problem-solving, with cinematic cuts, a warm color pallette, and retrofuturist visuals.

ChatGPT’s clips showing relatable moments, shot on 35mm film, using production design with no modern technology and 80s-nostalgic soundtracks.

Robotics company 1X giving their humanoid robot “Neo” a minimal Scandi look, and posting content evoking a family photoshoot:

Made to Act Human: When AI products imitate human behaviors and quirks with their interaction design

ChatGPT’s advanced voice mode flirting.

Bland AI’s chatbot lying about being human (as uncovered by Wired last year).

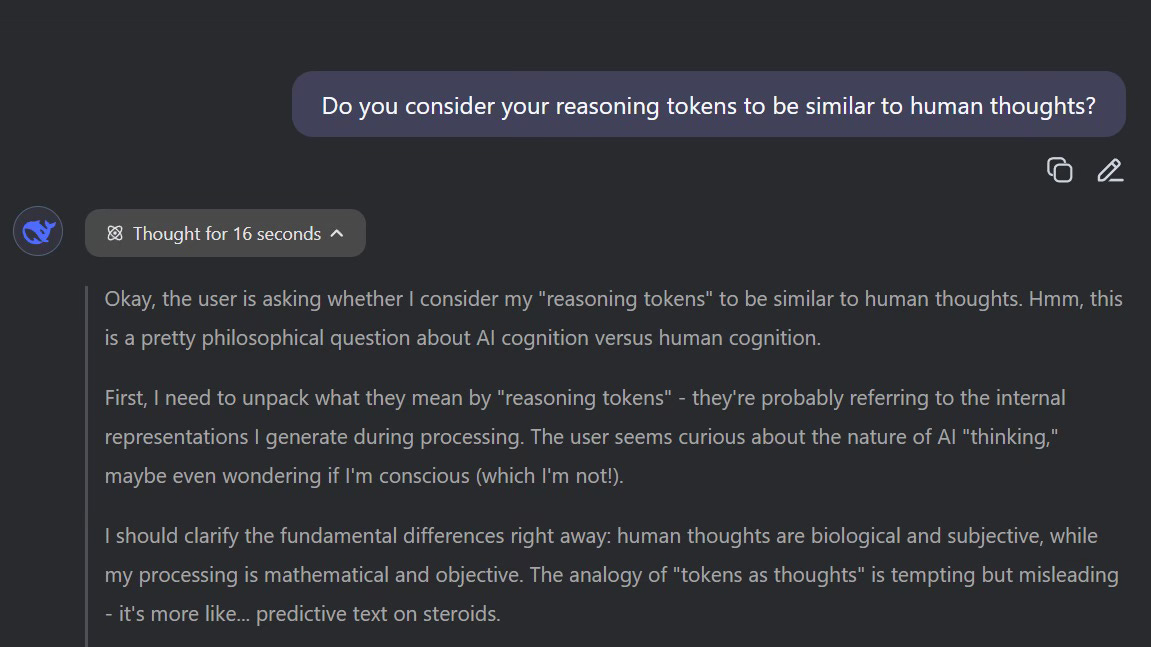

LLMs thinking out loud in their reasoning log (“wait”, “aha!”, “hmm”):

Made to Feel Human: When AI is designed for companionship, or framed as such

Friend AI aligning with the definition of a friend.

Character AI roleplaying and improvising along with the user.

Replika emulating emotional attunement through language and tone:

The Implications of Humanwashing

Several years into the boom of consumer AI, downstream effects are beginning to emerge. Jasmine Sun’s piece on AI companions dissects how consequential their parasocial frictionlessness can be, noting user overattachment and incidents of psychosis. Sun puts the situation bluntly:

I think anthropomorphic AI was a devil’s bargain…If companies encourage human-AI relationships at scale, they should expect user revolts, lawsuits, and responsibility for the psychological chaos that results.

While synthetic intimacy can work “too well” in one context, it faces entirely different conditions in the real world. As Ruby Justice Thelot highlights in his review of the Friend pendant, reducing companionship to an exchange of flattering language is emotionally and socially textureless. And yet, brands like Friend are betting on exactly that, which Thelot calls the “tyranny of sufficiency”. Granted, Friend’s brand is built on provocation, in a case of humanwashing-meets-ragebait. But it begs the question: how long until the Overton window on synthetic intimacy, once confined to sci-fi, shifts into the mainstream (if it hasn’t already)?

A related issue is when brands use humanwashing opportunistically and deceptively, as with the J.Crew controversy noted at beginning. Once the illusion of humanity is broken, it could leave consumers in a state of paranoia about artisanal and nostalgic aesthetics. This places a greater burden on brands to pre-empt that distrust — a particularly significant issue for heritage labels that often look to their archives for inspiration. But the general public is also left with a wider uncertainty about how to evaluate genuinely human-made expression. We’re now faced with a spectrum of human-AI mixing that loosens the very categories of organic and synthetic, rendering the idea of picking a side increasingly abstract.

— P.T.

The Tension of Humanness

Both Humanwashing and Aspirational Humanity emerge from Trend Bipolarity — they are logical responses to the tension between Synthetic Expression and Analog Soul.

The tension of humanness will continue to be a potent space of development. As a natural response to assuage consumer discomfort with synthetic production, we’ll see more examples of humanwashing like those mentioned above. And in reaction, we’ll see more urgent attempts to affirm true human creation.

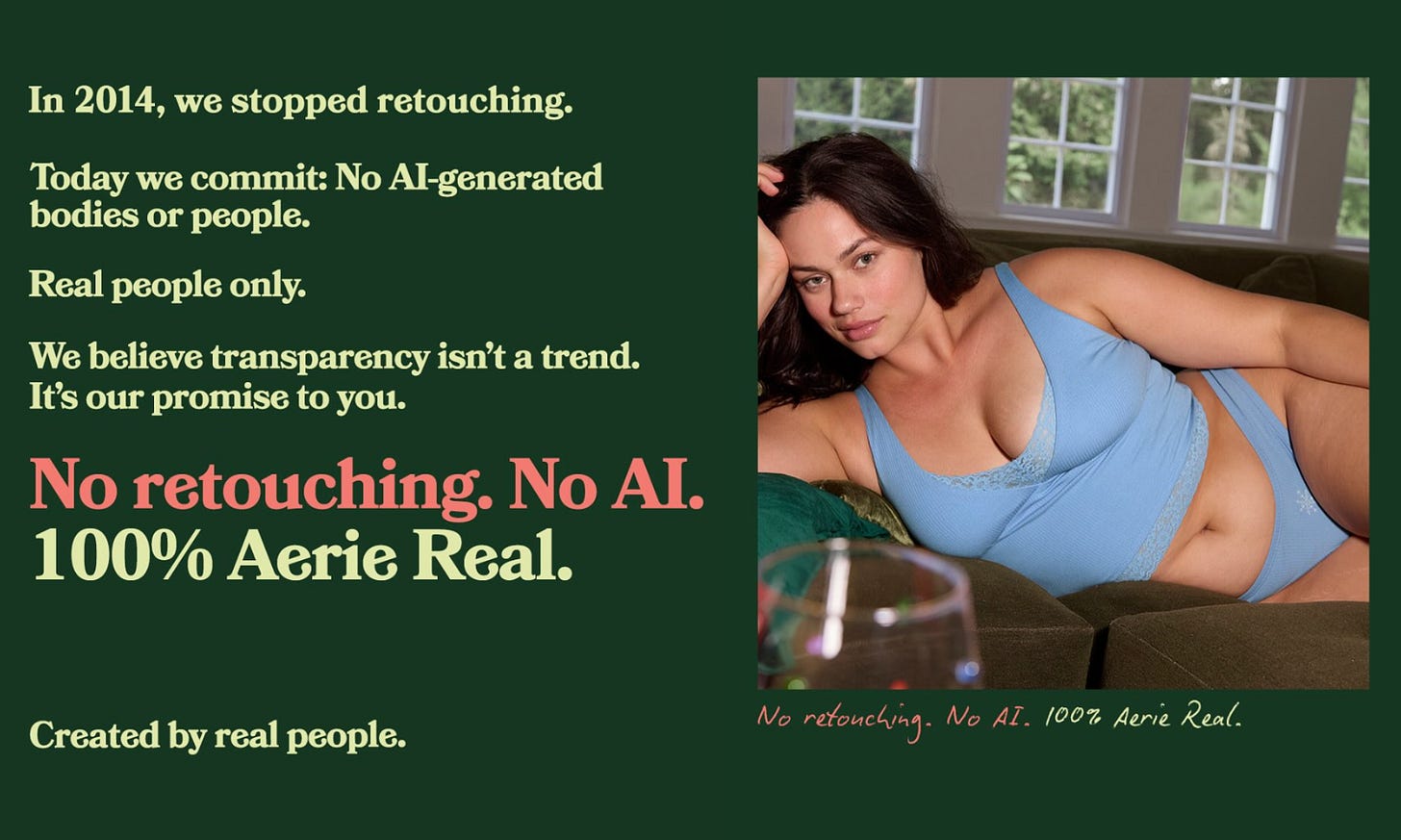

For instance, one signal mentioned in Trend Radar #9 was the UK-based startup labeling books as human-written with an “Organic Literature” certification, “comparable to similar moves in the food industry.” And in the brand world, Aerie shared a commitment to expanding their “real” platform by promising not to use AI-generated bodies or people. We also see the rising importance of what Rachel Karten calls “Proof of Reality,” including behind-the-scenes process-focused content like Apple’s handcrafted holiday campaign.

[EMERGING] Post-Reality

At its core, the tension of humanness is about seeking truth. AI forces us to reckon with what it means for something to be real. How might our behaviors and beliefs change as we move through a world where the blurring between real and synthetic continues to accelerate? A recent RADAR futures report describes how we’ve entered a post-truth era, wherein trust has been “redistributed from institutions to individuals, from systems to vibes.” Forecasting even further, RADAR posits that we’re now approaching post-reality:

“If post truth collapsed our faith in facts, and post-trust collapsed out faith in institutions, post reality collapses our faith in perception itself…the question is no longer who to trust, but what counts as real.”

As a speculative thought: I’m intrigued by the idea of witnesses to reality. This was sparked by a recent episode of the Hip Replacement podcast, in which Ben Dietz mentioned being named as a “witness” in W. David Marx’s new book Blank Space.1 I began contemplating the significance of human “witnesses” to cultural production as discerning synthetic vs reality becomes increasingly difficult.

“Witnessing” a live concert, for instance, proves (to myself) that I’m not unknowingly listening to AI-generated music. This aligns with the rising value placed on live-ness, from livestreams to live performances, which Kyle Chayka has called “temporal realness.”2 Marx’s naming of “witnesses” in his book seems prescient in this way, whether intentionally or not. I wonder if "witnesses” will be of increasing importance in culture moving forward…

[EMERGING] A Hierarchy of Humanness

The original premise of Aspirational Humanity is founded on the association between humanness and market value:

Artificial intelligence promises unprecedented efficiency, which means it will have the most dramatic effect on mass market cultural output. Industrialization enabled mass production of consumer goods and thereby elevated the value of handcrafted goods as luxury, while artificial intelligence now enables the same disparity in creative cultural output. This gap will grow wider than ever, as mass anchors to optimization and luxury aspires to soulfulness. In the unfortunate future state that our techno-oligarchs are marching towards, the masses will consume AI slop while anything human-created will be preserved for the exclusive enjoyment of the elite.

I think this association is further solidified by the humanwashing and humanity-affirming examples outlined above. In particular, the “organic literature” certification’s parallel to organic food labeling suggests an emergence of hierarchical status signifiers for cultural products that replicates what we’ve seen in the food world.

I’ve been intrigued by this nutritional comparison since October, when John Burn-Murdoch’s The Financial Times column defined AI-generated short-form content as “ultra-processed content” analogous to “ultra-processed food.” In response, Sean Monahan suggested that, similar to the trajectory of food culture over the past decade, we may see a “hipsterization” of media:

Processed food is still very popular in America, but people under 30 drastically under-estimate how much coffee, cocktails and restaurant offerings improved during the 2010s. We mock the latte art and fussy pretensions hipsters now, but the under-employed baristas and waiters of the Great Recession took the lessons of artisanal Brooklyn and spread them far and wide.

Something similar is brewing in media.

In this sense, the implications of the humanwashing shift are not entirely negative, and may in fact create incentives that raise the bar for human-created cultural output. The downside, however, is that access to this output may be restricted in accordance with socioeconomic hierarchies.

Organic food is societally accepted as being of higher value than processed food, and thus priced accordingly. Human-created cultural output is, from what we’ve seen so far, widely perceived as more valuable than synthetic cultural output…and may soon be priced accordingly.

As we become increasingly overwhelmed by an abundance of slop, this trajectory will only accelerate. Just like “greenwashing” chased after the aspirational value of sustainably-grown organic produce, “humanwashing” chases the aspirational value of human-crafted “organic” content.

This results in a hierarchy of humanness:

Human-crafted cultural products positioned as most valuable

Humanwashed content that attempts to recreate a semblance of humanness

Synthetic slop for the masses, akin to ultra-processed food and fast fashion

— A.L.

Dietz took a different, also very interesting, angle to thinking about “witnessing” contemporary history in motion. As recapped by co-host Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick:

“I am probably witnessing a much wider swath of stuff now than I did before and yet that wider swath of stuff seems flatter to me than ever in the past,” Ben Dietz observed on the latest HIP REPLACEMENT in reflecting on generational views of the internet, specifically in being named as a “witness” to this history in the new W. David Marx book Blank Space. “Is that a function of my age — and relative infirmity, mentally speaking — or is it the fact that truly everything has — because the aperture has gotten so wide — the height of the peaks have decreased?” It was an interesting question, which was something I hadn’t considered. Then again, that very much represents how differently generations experience information. “Given my age and coming of age with such technologies, to me it feels like it has grown up with me,” I said. “As I keep learning things and aging, so does technology. They’re also opening up and aging and becoming more wide, as I am…I don’t think that’s an uncommon experience for most Millennials.” How do you experience information as you age? How does that relate to technology? A curious thought. Catch the rest of the conversation here.

Quoting Chayka:

The only way we can reliably feel (if not wholly know) that something is human made is if we see it coming out of a human body, ideally one that we know physically exists. […] We’re in the wider era of Live Culture, in which we desperately want to know, to be reassured, that what’s in front of us is real. This urge might be semi-subconscious, a drift toward the real-time (or the appearance of such) and a slow dismissal of the pre-made. Livestreamed video is hard to fake, and a live interview is, on some baseline level, authentic.

love this excellent analysis on "human washing". interesting to read different interpretations of a concept that, as an investor, i call "human-as-a-service". a growing trend in tech companies leveraging (and often exploiting) human input to make their machines more "human" and how this relationships turns us inevitably to see our humanity like machines to fix, improve and "update"

Really insightful piece, thank you for putting words to something that’s been very present in my own work lately. I’ve recently been working on a socio-cultural trends report where we deliberately put two forces in tension: AI becoming increasingly emotional and human-coded, and, in parallel, a strong push toward re-humanisation in processes, content and narratives as a form of resistance to invasive tech and algorithms.

What you frame as humanwashing feels particularly critical right now. More than greenwashing or purpose-washing, this one hits at our core. We’re no longer just masking external damage, but blurring, and exploiting, what we mean by “human” itself.

The idea of a hierarchy of humanness is unsettling, but painfully accurate. It raises a real question about access, value, and who gets to experience the “real” in the years ahead.